Written by: Umme Salma Anee, Masroor Salauddin, Sadika Afrin, Faiaz Chowdhury, Nabila Binte Jahan, Deepa Barua, Rumana Huque, Helen Elsey

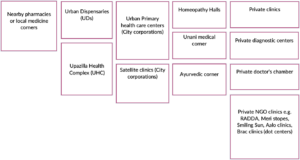

Urban regions in Bangladesh are now more densely populated as a result of migration and industrialization. With a population rise of 3.26% from 2022 to 2023, Dhaka, the country’s largest metropolis that is growing day by day, now has 23,210,000 residents 1. There are a variety of urban primary health care providers within urban areas, including2

Figure: A table displaying the list of urban primary health care facilities

* Primary health care is provided by urban dispensaries (UDs) in urban environments and by Upazilla Health Complex (UHCs) in rural ones 3. Throughout the entire city of Dhaka, there is solely one UHC that also serves few more services than the UDs including the cervical screening, breast feeding, diarrhea, and baby-friendly Anti-Natal Care (ANC) corners, as well as the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) corner 4. These are crucial for strengthening the urban health system in terms of giving the urban population primary healthcare services.

History: Urban dispensaries (UDs) in Bangladesh have played a crucial role in providing healthcare services to the population in urban areas. While the concept of dispensaries has a long history in Bangladesh, the establishment and development of urban dispensaries have evolved over time. Dispensaries were first used in Bangladesh during the colonial era, when the British offered basic medical services 5. The British colonial authorities and the local elites were the main customers of hese early dispensaries. They were mostly found in large cities like Kolkata (then a part of British India), Chittagong, and Dhaka. The newly formed East Pakistan (which eventually became Bangladesh) experienced several difficulties in providing adequate healthcare to its expanding population after gaining independence from British authority in 1947 and then from Pakistan in 1972. To meet the healthcare demands of the urban population, Bangladesh government established dispensaries in urban sittings since 2000 6.

As a consequence of the establishment and administration of dispensaries in various urban areas throughout the country, the government has continued to collaborate with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and private healthcare providers to strengthen urban dispensaries and provide health care services to all urban residents. Several regional and global non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have frequently backed the provision of healthcare services in urban dispensaries (UDs) through programs with varying lengths of time. The system’s health initiatives work to promote all primary healthcare, including basic diagnostics, preventive care, common illness, and non-communicable disease (NCD) services, as being accessible, affordable, and readily available to all levels of the population.

This information was obtained from the health facility assessment survey on preparedness of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) services management in urban primary health care facilities entire Dhaka city. The survey was conducted as part of the CHORUS research project on Strengthening urban primary health care system to deliver essential Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) care to urban poor at the ARK foundation for the CHORUS urban health initiative.

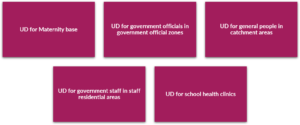

Location: Government Outdoor Dispensary (GOD) is another name of Urban Dispensaries (UDs). Currently, there are (19) Urban Dispensaries (UDs) in the entire city of Dhaka, which are overseen by the Dhaka Civil Surgeon in the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). In Dhaka city, One, known as a maternal dispensary, offers services for women’s and children’s health along with other services. Other UDs run school health clinics in various regions of schools. Additionally, some UDs work in primarily for government officials of their official zones, while other UDs tend to ordinary urban dwellers of various catchment areas in the entire city. In accordance with the region of UD, all are shown in a list that is given below:

Figure: UDs in several areas in the entire Dhaka city

Services Delivery 7: During the health facility assessment survey period, it was observed that all UDs at different tiers were capable of providing a variety of services, such as the early detection of conditions (Seasonal Fever, Diarrhea, Skin diseases-scabies), reproductive health, counseling, vaccinations, screening, diagnostic, and referral to other centers, in addition to the comprehensive service delivery package of maternity issues, child care and adolescent health. All of the previously listed services are offered to clients at no cost, in contrast to other primary healthcare settings like NGO clinics or private practices. Regarding those patients come here to obtain their medications for free who have previously been diagnosed with NCDs such as hypertension or diabetes from outside diagnostic centers.

As all UDs are only equipped for primary healthcare services, the UD providers refer the most serious cases to adjacent government tertiary institutions such Kurmitola Medical Hospital, Shaheed Suhrawardy Medical College or Dhaka Medical College and so forth.

Figure: Maternity clinic and dispensary in catchment area

Additionally, a few particular health services such as leprosy treatment or NCD care or Tuberculosis (TB) is obtainable in UDs in co-ordination with NGOs like the Damien Foundation, Marie-stopes, ARK foundation, ICDDRB. For example, a small team (from Damien Foundation) working on leprosy care at the UDs for two days a week has taken samples, diagnosed and treated patients, and given counseling and medication door-to-door. As well, monthly mobile medical campaigns are also organized by UD around the city of Dhaka in an array of congested regions, including the bus or train station, school premises, roadside, and local fish and vegetable market.

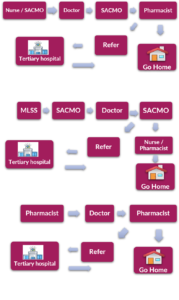

Health Workforce 7: Each UD has a medical team that includes a doctor, senior nurses, a Sub Assistant Community Medical Officer (SACMO), Medical Lower Subordinate Staff (MLSS) and a pharmacist. However, existing healthcare professionals require additional training on a variety of aspects, including NCD, to enhance their skill sets.

Along with their tasks at UDs, the government frequently dispatches health care personnel on short notice for special assignments regarding school exams, medical camps for national job exams, and health inspections for Cabinet members or foreign guests. As a consequence of this, there is a scarcity of personnel to manage the UDs, and at the same time, client access to UD health care has altered. When a client come to UDs for health service, he/she follows the care pathway according to the availability of the health care providers shown below:

Figure: The patient’s path to receiving care in UD is determined by the availability of health care providers.

Health Information System 7: Together with a pharmacist, a SACMO maintains records and reports for all monitoring paperwork, including client information, staff attendance logs, medication inventory forms, and requisition for supplies and equipment. These are kept in a number of register books such as patient registration books, medicine stock register books, medicine supply register books, and others for all services. Along with explaining how they update the register books every day, they also gave us a demonstration.

Medication and Equipment 7: Additionally, UDs have a modest amount of medications as a plenty of patients come here to especially get treatment for several health issues such as common cold, skin issues, hypertension. The patients often become rude with UD medical teams when they do not get their desire medicines as they have an affinity to come frequently in their adjacent urban dispensaries (UDs). There are also available essential functioning equipment’s such as sphygmomanometer, manual blood pressure machine, adult weight and height scale, thermometer, glucometer and glucose test strips.

Figure: Urban dispensary in the government staff quarter

Leadership and Governance 7: In the interim, government officials such as the civil surgeon of Dhaka City (CS), a team from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW), a team of Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) and International Non-Government Organisations (INGOs) among others, have often surveilled UDs.

Figure: School health clinic

Challenges: The UD medical team shared their experiences about providing health services to numerous clients (80 to 100) each day through a shortage of medical professionals and staffs. The UD team has met several difficulties due to the high number of patients using their services, particularly when staff members are absent due to illness or family issues or leave. To ignore their problems and strive to make their clients happy, the UD team nevertheless carried on offering healthcare services every day. However, the majority of clients are resident of nearby slum and non-slum regions including the transgender population. People who live in Bihari camps, workers, and residents of adjacent government staff quarters are very often afflicted with scabies and fungal infections as a results of having to live informal settlements that have no or limited access to clean water, sanitation and waste clearance and are overcrowded. Bihari are the Indians, or Pakistani people, who remained in various parts of Dhaka city following Bangladesh’s independence. They reside in what are known as the Bihari camps, a slum8. In addition, the majority of maternity services such as anti-natal care (ANC), normal delivery, with the exception of Post Natal Care (PNC), were unavailable during the COVID situation at the maternity UD clinics. The government announced that this service will be made available promptly, yet there is only one maternity UD in the entire city of Dhaka. Even though most UDs have inadequate space to provide services and have fewer personnel in many fields, they have managed to provide all services from one or two rooms.

Conclusion and Recommendation: The government of Bangladesh has made significant contributions with its urban dispensaries, which should be strengthened to advance the urban health system. If a part of the responsibilities the outdoor departments of tertiary govt. hospitals are shifted to the government UDs, it will lessen the burden on the government tertiary hospitals in Dhaka city. To fulfill their respective assigned responsibilities in a sustained and efficient way, the two Ministries (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW); Ministry of Local Government, Rural and Development Cooperatives (MOLGRDC)) need to build a sustainable coordinating mechanism through a consultative approach. Additionally, MOHFW has been addressing this challenge in order to collectively assess, map, project, and plan Health, Population and Nutrition (HPN) services in urban areas. Overall, urban dispensaries in Bangladesh have evolved from their infancy to become vital healthcare facilities that will significantly expand urban residents’ access to primary healthcare.

This blog has also been published on CHORUS website. Read Here

Reference:

- Dhaka, Bangladesh Metro Area Population 1950-2023; https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/20119/dhaka/population

- Bangladesh Health Facility Survey, 2017, https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA28/SPA28.pdf

- Urban Health, Community based health care, DGHS, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, http://www.communityclinic.gov.bd/urban-health-page.php

- DGHS, Tejgaon Health Complex, Dhaka, physical structure; http://facilityregistry.dghs.gov.bd/org_profile.php?org_code=10000057

- Public Health in British India: A Brief Account of the History of Medical Services and Disease Prevention in Colonial India, Muhammad Umair Mushtaq, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2763662/pdf/IJCM-34-6.pdf

- Primary Health Care Systems (Primasys): Case study from Bangladesh. WHO-HIS-HSR-17.12-eng.pdf

- Monitoring the building blocks of health system: A handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. World Health Organization (WHO), 2010. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258734/9789241564052-eng.pdf

- Altaf Parvez, what is to be done with ‘stranded Pakistanis’? 2021, prothom alo English. https://en.prothomalo.com/opinion/what-is-to-be-done-with-stranded-pakistanis